Not so CIPLE: A test-taker's tale

I took the A2-level European Portuguese proficiency exam for non-native speakers. In this post, I share how I prepared, how it went, and what scores I got, plus a critique of the exam itself.

On April 12, 2025, after eight months of focused, self-directed, technology-mediated language learning, weeks of waiting for the chance to register, and a month of exam-specific preparation, I sat for the Certificado Inicial de Português Língua Estrangeira—also known as CIPLE—a much-discussed and often dreaded language test for non-native speakers of European Portuguese (EP).

The CIPLE is the official exam used to certify A2-level1 proficiency in EP, a certification often required in applications for Portuguese citizenship and permanent residency. Its stated purpose is to assess the test-taker’s ability to handle basic, everyday communication. It covers reading, writing, listening, and speaking skills.

This post tells the story of why I took it, how I prepared, what the test was like, how I performed, and what questions and doubts I was left with afterward about the CIPLE.

Why I took it

I decided to take the CIPLE for a few reasons. First, I wanted a challenge, and I liked that it provided me with a concrete, specific goal. I also wanted some objective, expert feedback to see if I was making progress after months of guiding my own learning.

Second, I was curious about the test itself. Some of my work involves language assessment, and I have colleagues at Iowa State University who are key figures in that field, so I’m familiar with some of the issues. I’d heard people talking about the CIPLE in ways that set it apart from other language proficiency tests I’m familiar with, such as TOEFL and IELTS; specifically, complaints from test-takers about the difficulty of the listening section and anxiety expressed by people trying to avoid the CIPLE through alternate, course-based pathways to A2 certification. I wanted to learn firsthand what this intimidating test was like and what all the fuss was about.

I did not take the CIPLE for immigration purposes. Because my wife is a Portuguese citizen, I have another route to citizenship that doesn’t require language certification.

How I’ve been studying EP

I started studying EP seriously in July 2024, when my family moved to Portugal for a one-year sabbatical. Since arriving, I’ve been devoting a bit of time each day to a self-guided2 and technology-based approach involving mainly the following resources:

PracticePortuguese.com. An online learning platform exclusively for EP, with learning units organized according to the CEFR levels and lots of content for listening practice. I’d completed all of the A1- and about half of the A2-level materials by the time I took the CIPLE.

Speaking-practice groups. These were groups I organized through a WhatsApp chat for expats living in the city of Porto and studying EP. The groups consisted of four to six learners, supported by a paid, native-speaking EP resource teacher. We would meet online or in person to practice oral communication, using tasks based on grammar points we’d covered in the A1 or A2 units in Practice Portuguese.

Spotify. A rich source of EP-language podcasts and music. I worked on listening skills using shows geared toward learners (for example, Portuguese with Leo), but also some non-pedagogical content, like a special interest program about Portuguese football. For help with the latter, I used Spotify’s Lyrics tool, which displays scrolling transcripts synced to the recording.

Linguno.com. Another online platform that supports learning a number of European languages. In particular, I made much use of Linguno’s highly customizable tools for practicing EP verb conjugations.

DeepL. A machine translation service that provides impressively accurate and natural-sounding translations. Although it’s not designed for language learning, I tried to use it in a way that supports my learning of EP.

iTalki. An online language instruction platform that connects tutors and learners, primarily for one-to-one lessons. I worked at different times with four different tutors, all of whom I liked very much. They were knowledgeable, engaging, and eager to help, but I realized after a while that the format wasn’t working for me, so I stopped.3

The two pillars of my approach were Practice Portuguese and the speaking-practice groups. The former was my primary source of input; the place where I got new language. The latter was where I could use that new language in communicative practice. The speaking-practice groups also gave me opportunities to meet new people, become part of a community of learners, and expand my social network in the country.

Registering and preparing for the exam

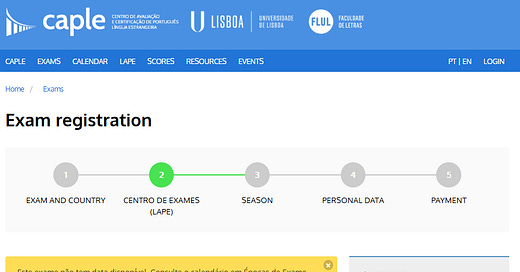

Initially, I wasn’t sure I’d even be able to register. There’s no email alert or announcement when registration opens, and when it does, spaces disappear quickly. You just have to keep checking back on the website of CAPLE (Centro de Avaliação de Português Língua Estrangeira), the Portuguese language proficiency assessment system. I checked daily, two or three times a day, for several weeks starting at the end of December when I was told to begin looking. A few days into January, the option to take the test in Lisbon on April 12 and some other dates suddenly appeared, and so I registered immediately.

Once I was signed up, I started gathering test preparation material, including descriptions of the exam, advice from past CIPLE takers that I found in the Practice Portuguese user forums and other venues, exam preparation books, and all the sample CIPLE test forms I could get my hands on. I posted messages to the WhatsApp chat and the Practice Portuguese forums seeking practice partners for the speaking component. I also created a custom CIPLE Prep Coach in ChatGPT to help with various exam-related tasks.

A month before the test date, I stepped away from my speaking-practice groups and began devoting all of my daily language-practice time to CIPLE prep. I did a bit of speaking practice with my new contacts, but quickly realized it was the other parts of the exam that I was less prepared for, so I started concentrating on those.

For the reading component, I used the practice materials in the CAPLE exam preparation books produced by LIDEL, a well-known publisher of educational and technical resources. Once I’d finished with the two CIPLE sample tests in the lower-level book, I moved on to the materials for the higher-level tests, including those in the B2-level book. Given my experience studying Classical Latin and Spanish in high school and college, reading felt easy to me, but I still wanted to get used to the types of texts and questions I would find on the exam.

Writing was more of a challenge. I’d done very little writing for communicative purposes up to that point, except for short texts and WhatsApp messages. To be sure, I had a lot of experience typing in Portuguese, having done many app-based grammar and vocabulary exercises, and I could produce all the accent marks on both physical and virtual keyboards. But the CIPLE is written by hand, and the writing tasks involve drafting messages to friends or landlords or lost-and-found departments, which was new to me. I was also told it was very important to stay within the specified word limits.

To prepare, I had my AI coach generate a large number of prompts like those used in the shorter and longer tasks in the CIPLE writing section. I’d write out my answers in pen and photograph them for submitting to the chatbot, which then gave me feedback.4 This feedback included a transcription of my original answer so I could see if the GPT had been able to make sense of my handwriting; an evaluation according to categories such as task completion, clarity of communication, and appropriate language; suggestions for improvement; and a reformulated version of my original that incorporated the suggestions.

For listening, I applied the same strategy as with reading, using the listening materials from the exam prep books. When I’d finished the A2 practice, I moved on to the B1 and B2 material. At the higher levels, the recordings and questions obviously became more difficult, but I was still able to make sense of a fair amount of it and get at least some of the answers correct. I’ll say more below about how effective this ended up being (long story short: not very).

My final bit of preparation was to set aside two days right before the test for mock exams taken under timed conditions. I sat at a desk with a test form, answer sheet, pen, pencil, eraser, and a timer spread out in front of me, trying to simulate the actual test environment so I could develop a feel for the pacing and mental focus I’d need for the real thing. (One of those mock tests happened at an Airbnb in Lisbon the day before the exam.) They weren’t perfect simulations, of course, but they gave me confidence and a clearer sense of how I’d need to manage my time on the day.

Test day

The test was held at NOVA University of Lisbon, in the eight-story Faculty of Social and Human Sciences (FCSH) building, which I’d already scoped out on Google Earth (and which, interestingly, resembles a giant open book). I arrived early to get the lay of the land, avoid last-minute stress, and give myself time for a final bit of reviewing.

At about 8:40 a.m., the staff began checking us in individually, confirming our IDs and registration details. We were then ushered into an auditorium where we’d take the combined reading-writing component and the listening component. We sat in assigned seats spaced widely to discourage wandering eyes. Two proctors (both women, presumably from the university) oversaw the exam. They were friendly but professional, giving instructions and fielding questions only in Portuguese. They went over the schedule, reminded us to use a pen for the writing part, and gave some other guidance. The exam started slightly behind schedule, a little after 9 a.m.

First came the reading-writing component. Reading involved 20 multiple-choice items, the first 10 based on short passages (text messages, advertisements, public notices, and so on), and the second 10 were divided between two longer texts. Unfortunately, I didn’t write down the topics of these texts after the test so that I could share them here, and I’ve since forgotten them, but they’re typically personal emails/postcards, personal narratives, work-related messages, or announcements of some sort. Although the texts and questions became more challenging as it went along, the reading component seemed very straightforward.

Writing involved two short tasks, the first requiring a response of 25–35 words and the second, 60–80 words. Again, I couldn’t tell you what my particular tasks were, but the first typically involves a note, message, announcement, or form-style text with a unidimensional purpose (for example, describing a lost item or making a reservation). The second, longer text involves three or four required content points incorporated into an email, postcard, or letter, for example, in which you describe a vacation or respond to a message from a friend.

The reading-writing section is allotted 75 minutes, and you can move back and forth between the two parts as you wish. I was careful to double-check my answers, knowing from experience as a test administrator that points are often lost to careless mistakes. I first wrote all of my answer choices on the test form itself and my written drafts on the provided scratch paper, then re-read and verified everything before transferring it over to the answer sheets. All that work took me right up to the end of the period.

We then had a short break, during which we could use the bathroom or grab some coffee from a vending machine. After that was listening.

The listening component followed the expected format. The first part comprised a number of short, 30- to 150-second recorded texts, some involving one speaker (for example, a train service announcement) and others multiple speakers (an interview with an immigrant from a Lusophone African country). There were 15 multiple-choice items in this part, two to five per text. We heard everything twice and were given some time to preview each text’s questions before listening to it, but it was all part of one 30-minute recording, and once playback started, there was no stopping or going back.

I struggled mightily. The listening material in the exam prep books had not prepared me for this, even the B2-level practice. All of those recordings had been scripted and voice-acted, as far as I could tell, but at least some of what I was now hearing was authentic, taken from radio programs or podcasts, which was clear from the way the interstitial music at the end cut off abruptly. I tried my best to take notes, but I could make very little sense of what I was hearing beyond the overall gist. I found myself guessing based on potential distractors in the answer choices; if I’d heard a word that appeared in a given choice, I’d try to choose another item.5

I had more luck on the second part. The remaining 10 listening items all involved matching. You hear 10 brief utterances and have to match each one to the context in which it occurred (for example, Aeroporto, Banco, or Consultório Médico). In contrast to the other audio, this material was clearly scripted and voice-acted, and thus easier to understand. I was able to use process of elimination to figure out two of the 10 that I wasn’t initially sure about. I remember thinking that, if I passed the CIPLE, it would be thanks to these items.

Coming out of the reading-writing section, I’d felt reasonably confident, but now I was rattled. And I wasn’t alone. I heard a number of heavy exhalations and puffed-cheek sighs as our answer sheets were collected—those universal sounds of resignation and defeat. My eyes met another guy’s as we left the auditorium, both shaking our heads, eyebrows raised, as if to say, “What the hell was that?” I had to pull myself together. I couldn’t spiral into a negative mindset because the speaking component was still ahead of me. I called my wife, and she and my son talked me back from the edge. Yet some doubt lingered, and it stayed with me until I finally got my results (see below).

The speaking component is what’s called a paired oral assessment. Two candidates are tested at the same time by two examiners. You interact alternately with one of the examiners and then with your candidate partner. Over 15 minutes, you have to (1) make a brief personal introduction, (2) perform a structured practical interaction with the examiner, such as role-playing ordering in a café or asking for directions, and then (3) join your partner in a short discussion based on an image- or text-based prompt.

The speaking test schedule had been projected at the front of the auditorium at the end of the listening test, showing assigned time slots and speaking partners. I’d been paired with a 20-something American woman who’d spent a study-abroad year in Brazil and who thus could speak quite fluently, though with a distinct Brazilian accent. We chatted for a while outside the building and settled on a few strategies, including using the informal tu form with each other to make things a bit easier grammar-wise. She lived nearby and went home to get something to eat, agreeing to meet inside a few minutes before our time slot. I used the time to review my speaking notes.

About ten minutes before our appointment, I went back inside. I was expecting a bit of a wait, but as soon as I arrived at the alcove outside the assigned classroom, one of the proctors came out and called my name. There’d been some schedule shuffling—maybe someone hadn’t appeared on time—and they were pulling the next test taker on the list. So I ended up going in early and being paired with another young woman, who was less fluent but still a strong speaker, and who spoke with an EP accent. This immediately put me more at ease.

After positioning us for the video recording (needed in case the two proctors couldn’t agree on our scores), we started. Following the brief introductions, my partner was asked to describe her daily routine, which she did admirably well. The proctor then asked me about where I lived. I tried to describe our apartment (how many rooms it has, where it’s located in Porto, what kind of neighborhood it’s in), but I got tongue-tied a few times trying to recall how to say roomy and the verb for to rent.

The final part, where my partner and I interacted, went much better. We were shown a handout depicting seven vacation options and asked to decide collaboratively which would be the best for a joint family trip. The options included a cruise, a camping trip, and an amusement park. The open-ended nature of this task made it fun for me. I got to be a little creative in my contributions, make some jokes, and bring in my real-life experience and opinions (including my aversion to cruises). We were genuinely communicating, not just performing, and I noticed smiles on the proctors’ faces. It felt good to end on a positive.

How I did

The CIPLE is graded on a 100-point scale, with results classified as Muito Bom (85–100%), Bom (70–84%), Suficiente (55–69%), and Insuficiente (below 55%). As these suggest, you need a minimum overall score of 55% to pass and earn the A2 certification. The exam is weighted differently across sections—Reading and Writing (45%), Listening (30%), and Speaking (25%)—with your performance in each component contributing proportionally to the final result. You can’t score below 25% on any section and still pass.

About seven weeks after taking the CIPLE, I received emailed instructions for accessing my results on the CAPLE website. Upon inputting my candidate code on the Exam Scores page, I learned that I had been classified as “Bom.”

Then, by accident, I discovered that if you press the print button on this page after retrieving your results, you get a breakdown of your scores for each section. Mine were:

Reading: 100

Writing: 70

Listening: 52

Speaking: 75

Based on these scores and the section weightings above, I calculated my overall score to be 72.6%,6 which positions me at the lower end of the “Bom” scale (Bomzinho, if you will). Still, I thought, not bad for about nine months’ worth of self-directed, in-country study, 1-2 hours a day, minus holidays and many weekends.

Some thoughts about the CIPLE

I was obviously pleased with my reading score and satisfied with the speaking score, given my bumpy start on that part of the test. I did worse than I thought on the writing part, and I guess I’ll never know exactly why. My listening score was about what I’d expected, but there’s something that still doesn’t sit right with me about it.

On the one hand, the listening section was clearly disproportionately difficult. While the writing and speaking tasks were challenging, they felt achievable and of a piece with each other and with the reading component. The listening part felt like it was from a different exam. As an applied linguist, I can’t help but question whether the listening section is functioning effectively from a psychometric standpoint. If a large number of test-takers can’t cope, it suggests the listening items may not be performing their intended function very well, which is to differentiate among levels of proficiency. A well-designed test should show a decent spread of scores, reflecting real-life variation in the abilities of the sample, rather than clustering at the lower end of the scale.

On the other hand, spoken European Portuguese is indeed very difficult for learners to make sense of; part of my sabbatical has been dedicated to researching the phonological and perceptual reasons why that is. That being the case, the difficulty of the listening test could be seen as a faithful reflection of real-world communicative demands. And maybe I and the other audible sighers in that auditorium weren’t representative of the whole. Some CIPLE takers—those working in Portugal in customer service, hospitality, or caregiving, for example—may be much more adept at understanding spoken EP based on their daily immersion in it. Maybe those of us complaining have fallen victim to a false-consensus effect, assuming everyone shares our struggles.

The problem is, there’s no way of knowing either way. Neither the staff at CAPLE and its partner institutions nor any independent researcher appears to have published anything about the exam that could be used to build a validity argument supporting its interpretations and uses.7 Searches in academic databases for CAPLE-focused research, formulated in English or Portuguese, turn up virtually nothing. A bibliography on the CAPLE website lists only the manuals and guidelines that were consulted in designing the exam, along with policy reports about immigration and some exam preparation books. The sole CAPLE-authored reference is mostly expository, explaining CAPLE’s institutional structure and methods; the only empirical data are test-taker demographics, motivations for taking CAPLE’s different exams, and exam distributions by proficiency level.

This is in contrast to the Celpe-Bras, the equivalent test of proficiency in Brazilian Portuguese, which has been the focus of comparatively much more research, as reflected in a 2019 review published in the leading language assessment journal. This review found evidence supporting the claim that the Celpe-Bras assesses real-world communication skills, but it also identified needed improvements, including making preparatory materials more accessible to all proficiency levels and ensuring greater clarity and consistency in its scoring rubrics. The CIPLE, which has been around longer than the Celpe-Bras, needs to be subjected to the same sort of scrutiny. In light of its high-stakes uses and the fact that demand for it is likely to increase, an evidence-based review of this exam is warranted and long overdue.

Further reading

For those interested in the points raised here, I have shared, or will soon be sharing, other posts related to:

how to use machine translation tools like DeepL to support language learning;

why, from a linguistics perspective, spoken European Portuguese is so hard to understand;

how I’m using generative AI in my language learning; and

why conventional language courses may no longer be the most efficient option for developing proficiency.

Thanks for reading … and good luck to anyone preparing for the CIPLE!

Have you taken the CIPLE, or are you planning to? What was your experience like? What’s been your biggest challenge in preparing? Any tips to share? What role has community (study groups, language exchanges, and so on) played in your preparations? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

A2 refers to the second level of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), a widely used system for describing language proficiency across six levels from A1 (beginner) to C2 (mastery). A2-level learners are considered “basic users” who are able to understand commonly used expressions related to immediate needs (for example, personal and family information), carry out simple, routine tasks involving direct exchanges, and describe familiar aspects of their background and surroundings.

I haven’t taken any formal courses for a few reasons. Until recently, I didn’t have the residency documentation needed to enroll in government-subsidized courses, nor did we have spare funds for expensive private classes, given our half-salaries during this sabbatical. In addition, I wanted my learning to contribute to my sabbatical research, which addresses informal, technology-mediated language learning in the so-called “digital wilds.” Finally, and relatedly, I’m trying out a model of language learning based on apps and supplementary skills-development groups as an alternative to conventional language courses.

This has nothing to do with the tutors themselves and everything to do with what goes on in my own head during tutoring. Regardless of what we were doing, I felt like I was constantly being assessed. It was hard to focus on the communication because I was preoccupied with how I was communicating: the mistakes I might be making, and more so, the repetitive language I was relying on. I haven’t given up on one-to-one tutoring, but I have to figure out how to make the format work for me.

I had my wife review this feedback, which she said was very good, especially in terms of grammatical correctness, although there were a few infelicities: errors that weren’t caught or unnatural-sounding suggestions. I’d like to think these accounted for my lower-than-expected writing score, but it’s much more likely to have been my own shortcomings.

CIPLE item writers are said to frequently incorporate distractors (plausible but incorrect options meant to test finer points of comprehension) into multiple-choice response options. These include words or phrases that appear verbatim in the reading or listening text, while the correct answer is formulated with a synonymous word or phrase.

The formula for the overall score as a weighted average (%) = (reading × 0.225) + (writing × 0.225) + (listening × 0.30) + (speaking × 0.25). Because reading and writing together account for 45%, we split that equally at 22.5% for each. Then, we can plug in my scores.

= (100 × 0.225) + (70 × 0.225) + (52 × 0.30) + (75 × 0.25)

= 22.5 + 15.75 + 15.6 + 18.75

= 72.6%Modern approaches to validation focus not on whether a test “measures what it’s supposed to” but rather the appropriateness of the inferences drawn from scores on the test and how those scores are used in real-world contexts. Establishing this kind of validity requires empirical evidence to demonstrate how well the test supports inferences underlying those interpretations and uses. For high-stakes exams like the CIPLE, which are used to make life-changing decisions about granting citizenship or permanent residency, publicizing this kind of evidence is critical. Published validity research could help resolve important questions, such as whether the tasks on the CIPLE accurately represent the language abilities that Portuguese society expects of someone at the A2 level; whether all sections of the test are sufficiently reliable; whether the scoring system works well across different types of learners, and so on.

Truly fascinating account, Jim. I’m really interested in finding out more about how you’ve used AI - so looking forward to that article! And parabens 👏👏👏

Congratulations on passing the CIPLE and for doing so well on it! Your excellent account of the process validated my belief that I did well to avoid it. I’m as dedicated to being proficient in EP (also an American immigrant), but I did the course that gave me the certificate. It was a real trial of endurance and I didn’t learn well there, but I’ll use some of your tips to keep improving on my own. Muito obrigada!